– To mark the centenary of Greimas’s birth, the Lithuanian Parliament has declared 2017 the Year of Algirdas Julius Greimas, which followed the inclusion of this date into the list of anniversaries observed by UNESCO. What significance does Greimas have to Lithuania?

There are two Greimases. There’s the world-renowned scholar and the founder of semiotics whose importance to the humanities and social sciences he himself compared to that of mathematics for the natural sciences. Greimas has left a body of excellent examples of semiotic readings of texts. Alongside this corpus of his work, there are also his studies in Lithuanian mythology, carried out in the framework defined by Georges Dumézil and Claude Lévi-Strauss and reaching some highly significant conclusions.

The Paris – or the Greimasienne – school of semiotics is a living and vibrant school, whose methods are creatively used and elaborated in Research Centres scattered across the world. Surely, semiotics is one of many available choices for scholars in humanities, and it interacts with other theoretical approaches, such as phenomenology, for example.

It is the other identity of Greimas that is of utmost importance to Lithuanian culture: of Greimas as the secularist liberal writer who, over the years, wrote a great many essays for the Lithuanian diaspora press on social, cultural and political issues, and even published some travel writing. His letters are incredibly interesting, giving us a glimpse into the breadth and depth of his remarkable personality. This side of Greimas is still somewhat unknown to Lithuanian readers, since this part of his writing is scattered across periodicals and archives.

After the country regained independence, Greimas did all he could to open Lithuania to the Western culture, facilitate intellectual exchange and collaboration between scholars. He used to send his colleagues to Lithuania and invite Lithuanian academics to French universities. He also proposed ambitious projects for the future of Lithuanian culture, encouraged cultural publishing and advised on it, and contributed his own polemical writing to the periodical press.

– What are Greimas’s most outstanding works and contributions to the theory of semiotics? Why is he relevant today?

Greimas’ ambition was to create a general theory of meaning: to explain how meaning emerges, how it exists and dies away. He laid the foundations for this theory in “Structural Semantics” (1966) where he started off from the units studied by traditional linguistics – words and sentences – and moved on to the semantics of discourse, or narrative grammar. He later published his other fundamental works: “On Meaning” (1970), “Maupassant. The Semiotics of Text: Practical Exercises” (1976), a sizeable book devoted to a detailed analysis of a short story of just a few pages, “The Social Sciences. A Semiotic View” (1976), “Semiotics and Language: An Analytical Dictionary” (1979, with Joseph Courtés), “On Meaning II” (1983). These works make the so-called semiotic canon, but in fact every subsequent book pushes the theory a step forward.

Later on, expanding the field of inquiry and opening up to new approaches, Greimas and his school shifted focus from the object to the subject, from actions to states of being. This shift places primary emphasis on esthesis, which is the sensual aesthetic link between the human being and the world (“On Imperfection”, 1987). The analysis of the sensual dimension of meaning brings to light modulations of different states of the spirit (“The Semiotics of Passions”, published with Jacques Fontanille in 1991).

To us, the Greimasienne semiotics appears to be relevant as much as scholars in the humanities and social sciences raise epistemological and methodological questions and draw on semiotics to find answers to them. Regretfully, it is not only theory itself that is lacking in our current scholarly practices in the humanities and social sciences but also a sense of this lack, as research in these fields is driven predominantly by the researcher’s spontaneity and immediate practical purposes. We still need to discover Greimas.

– How does Vilnius University – namely, the A.J.Greimas Centre for Semiotics and Literary Theory – cultivate and develop Greimas’s ideas?

Our Centre was founded, in wake of an initiative from Greimas himself, in 1992 by the then Rector of Vilnius University Rolandas Pavilionis, so we are celebrating our twenty-fifth anniversary this year. All these years, we have been organising the Interdisciplinary Seminar, which is being attended not only by our students and graduates, but by everyone interested, some people coming for years. It is a creative workshop where people can learn: we scrutinise theoretical writings by Greimas and other semioticians and analyse a great variety of texts – literary works, but also visual, plastic expressions, and advertisements. We have even examined restaurant menus, perfume bottles, and photographs of political figures. Semiotics is not just a theory, it is practice too, which has to be acquired and mastered as a skill to be applied.

As scholars, we also translate semiotic works and write original articles and books in semiotics. We have a quite substantial body of Greimas’s work in Lithuanian, so there is enough material to study. We publish the journal “Semiotics”, which started in print and is now being published online. Our work in progress, the online dictionary of literary terms “Avantekstas”, is available for use (and very useful!). The Centre offer a Master’s programme in semiotics, which is the only such programme in Lithuania, and some of our graduates are already working on their PhD theses in the field.

– Greimas delivered a series of lectures at Vilnius University back in 1971 and 1979, at the time when it was still behind the Iron Curtain. Do you recall any memorable moments or the atmosphere from them?

Both occasions were unique experiences. Amidst the mediocrity of Soviet life, his delivery of academic talk itself was making an enormous impression – we had never heard this kind of the Lithuanian language before. When Greimas spoke of his “semiotic project” (this was what he called it), I found it rather hard to follow. But rereading the transcripts of his lectures now, I am surprised – they are so transparent and clear! We listened to Greimas in auditoria packed with all kinds of people. When he gave his reading of the founding myth of Vilnius, he himself had an air of a mythical figure, a semi-god. On Greimas’s second visit, the authorities played in the style of KGB, spreading false information that the lecture would take place on Čiurlionis Street and making the whole the crowd of audience run across town back to the Central Campus to hear it…

– Are there any more links between Greimas and Vilnius University?

Greimas stayed in touch with Zigmas Zinkevičius, professor of linguistics, with the Rector Jonas Kubilius and others, and he sent books for the university library. Rector Rolandas Pavilionis went to Paris for a fellowship under Greimas, who then in his letters called him a “Knight”. He urged Pavilionis to found the Faculty of Philosophy and a Department of Modern Linguistics and hire people who “had things to say” rather than those holding formal degrees. At the time of rebuilding independent Lithuania, Greimas used every opportunity to send to Lithuania his fellows semioticians and helped us build international academic networks. It is hard to imagine today the isolation and void in which we lived, and how much it meant to us back then.

– Have you had a chance to meet Greimas personally a lot?

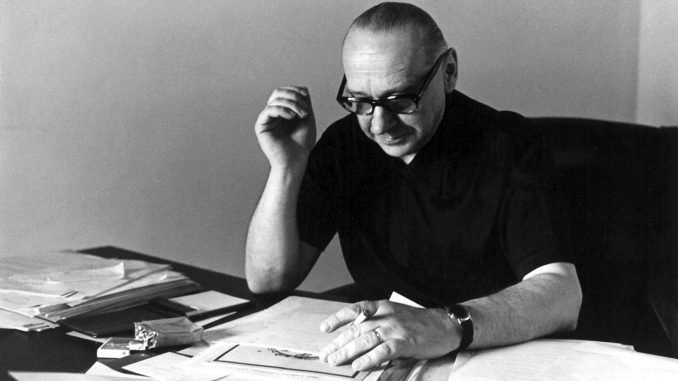

Not much. In 1988, I saw him at his famous office on Rue Monsieur Le Prince (in Paris) and later visited him at his apartment on Palais Royal, from which I remember a semi-circular window with a view of then still young trees in a French park. I found it hard to have a conversation with him – I knew nothing of semiotics, I was shy and humbled by his authority. A brown dog named Rudis was running around in the room, and I asked Greimas about its Lithuanian name. Greimas replied as he did to many: “schizophrenia.” For him, this meant living in two cultural worlds simultaneously, the French and the Lithuanian one.

Greimas urged us to start a journal, “Baltos Lankos” and had ambitious plans for it. He mostly corresponded with Saulius Žukas, asking him to show me a letter at times, while I have received just a few letters directly. Greimas communicated in a very comprehensive manner, he was pragmatic, focused, and did not want to waste any time on the minor details we were struggling with. He placed on us the responsibility for publishing the journal and advised on the contents as long as he was alive.

– What major events are planned to celebrate the year of Algirdas Julius Greimas?

There is an official part to start with: there have been a commemorative celebration at Vilnius Town Hall, several exhibitions, and lecture rooms have been named after Greimas at Vilnius University and Šiauliai University.

The most important part of the Greimas celebrations, in my view, consists of publishing projects. With French semioticians, we are working on a two-volume study “Algirdas Julius Greimas: The Person and Ideas”, there are projects for publishing a Lithuanian translation of the first volume of Greimas’s biography by Thomas F. Broden of Purdue University, a collection of Greimas’s essays compiled by Greimas himself but never published, and a Lithuanian translation of a key work of his, “Maupassant”.

UNESCO headquarters in Paris will host an International Congress in May, and there is a session being dedicated to Greimas at the International Semiotics Congress in Kaunas in June. More conferences have been planned, and we are planning a tour across Lithuanian universities.

The Greimas Centre has accumulated a fair deal of Greimas’s biographical documents. We intend to continue working on this project and publish selected material on our open-access website semiotika.lt. A website dedicated specifically to the Year of Greimas, www.greimas.eu, is to be launched soon.

Interviewed by Agnė Grinevičiūtė.

The interview is part of the project “Algirdas Julius Greimas: Ideas” funded by the Science Council of Lithuania (LIP-016/2016/LSS-180000-402).

Translated from Lithuanian by Justinas Šuliokas, edited by Jūratė Levina.

Be the first to comment