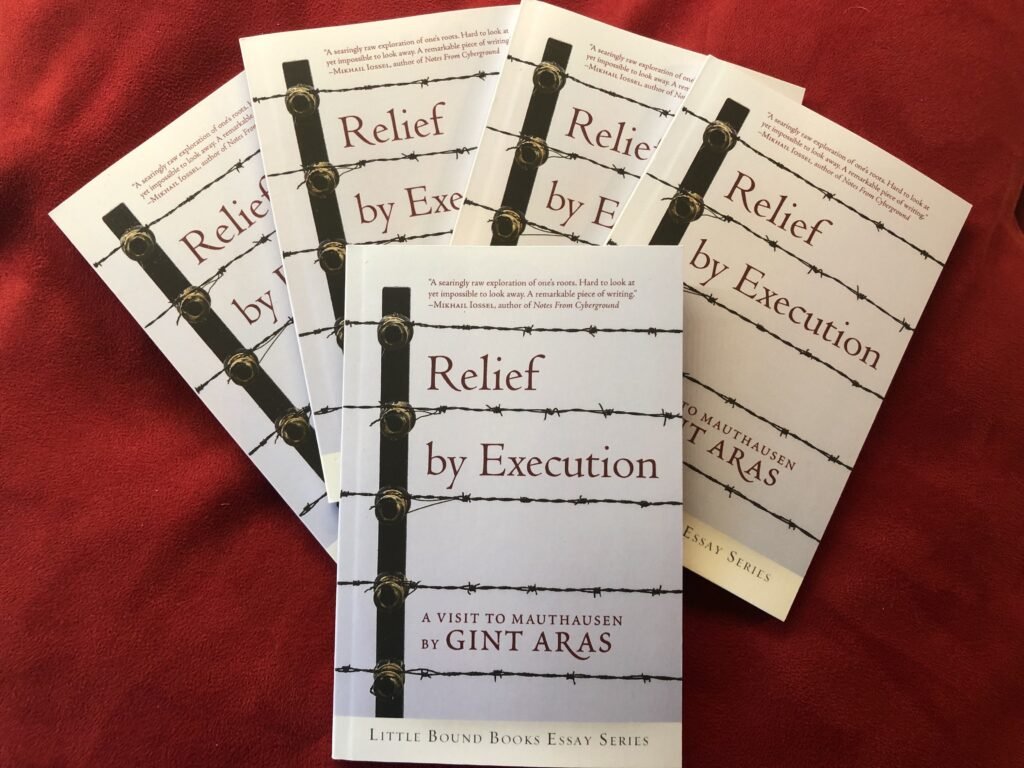

Rising literary talent, Gint Aras (Karolis Gintaras Žukauskas,) shares stories created of raw natural artistry and studied precision. A Lithuanian-American native of Chicago’s suburb of Cicero, he’s the author of the novels, Finding the Moon in Sugar and The Fugue, and also a forthcoming memoir, Relief by Execution: A Visit to Mauthausen (Homebound Publications, 2019).

An essay, Members Only: Marquette Park, will appear in an anthology titled The Chicago Neighborhood Guide (Belt Publications, 2019). Both works of non-fiction deal with, among other themes, racism and xenophobia in the Lithuanian diaspora.

Dmitry Samarov, writing for the Chicago Tribune, shared an accurate description of Gint’s writing style, and a short analysis of The Fugue:

“Rather than proceed chronologically, the story loops in on itself; episodes echo over decades and different people often seem to trade thoughts and threads of conversation as if picking them out of the ether. Over and over people strain to describe music by means of image, colors, and shapes standing in for notes as in synesthesia. Dreams described by one person are overtaken by another with no explanation, yet none is needed. Yuri becomes a sculptor just like his grand-uncle Benny, whom he’d never met; Lita tries to play music the same way Lars does, though they don’t know each other and never will; characters try repeatedly to confess and unburden themselves with little success. The forces that push them all this way and that are beyond any one individual’s will or control.”

Alexandra Kudukis. It’s more than a book, as the title suggests; it has musical elements/components and is really outstanding work. When I read your book back in 2016, I have to admit, I’d honestly never read anything quite like it. Could you share your process in creating the characters and the story for The Fugue?

Gint Aras: I was a graduate student living in New York when I started The Fugue. It was 2000, and after three years of life in Austria, I had been in the States for just over a year. I felt between planets, in a sense, which I think is important to the development of the book, primarily its themes of collapsing identity and sudden awakening, and the questions it poses—as Dmitry Samarov notes—regarding individuals’ agency over fate.

It still shocks me to remember that the novel began as a vignette to practice description. I described this imagined window made of broken beer bottles: brown and green glass soldered to wires of a chain link fence. It occurred to me that the window’s craftsman was probably more interesting than the object, and so Yuri Dilienko was born. He’s the main character in The Fugue.

I first imagined him as an Amsterdam squatter, perhaps a Soviet emigre, but he was really a shell …and, frankly, the outside artist who solders beauty out of refuse is cliché. At one point, I thought I’d abandoned him, but he kept coming back when I sat to write—he’d bother me as I showered, prepared food or took walks.

Obsessively, I started seeing him in my hometown, in Cicero, walking my childhood streets. Now he was a metals sculptor. He had a history: a Ukrainian father, Lithuanian mother, girlfriends, wounds, a deepening identity complete with criss-cross cultural and ethnic ties. He grew up Catholic, abandoned the faith, lost his family in a house fire, and then ended up serving time for murder, though his careful and sensitive consciousness seemed antithetical to violence and arson.

A character like this demands a novel, and I got excited when I saw the possibility for a multi-generational book. I loved the vignette at that time in my career, so I started stringing together little episodes, exploring other characters in Yuri’s family tree. Eventually, a post-war epic had developed, a meditation on guilt and convalescence.

Oh, and the window of bottle glass survived. It’s in the book.

It has been three years since your work was published. How have you changed as a writer since then?

Gint Aras: My life has changed in monumental ways, enough to shift my sense of self. My ex-wife had come out as a lesbian right around the time I had sold The Fugue; I had also taken dual citizenship at that time. Over the course of the past year, I got divorced and remarried. Then, my grandfather—he was responsible for my interest in stories and literature—died only months before reaching his 100th birthday.

All of these experiences intensified and matured my interest in the themes of death and love, how they relate to identity, memory, imagination, one’s sense of history, and one’s agency.

You practice Buddhism, which encompasses a variety of traditions, beliefs and spiritual practices, including meditation. Could you please share how you came to these beliefs, and the practice? Has it had an impact on your writing, if so, in which ways?

Gint Aras: In my forthcoming book, Relief by Execution: A Visit to Mauthausen, I explain that a traumatic experience led me to meditation practice. I got robbed at gunpoint in 2010. It happened in a convenience store, and during that robbery, I was certain the thieves were going to kill me.

The aftermath was a horror trip. I got diagnosed with PTSD, and my life changed. I don’t want to give away spoilers, but I grew up with an abusive alcoholic, in a family system whose purpose was to keep up appearances. Once I had children of my own, I feared keeping up the appearance of a “sound and proper family” would send my kids into the very madness that had overwhelmed me. To heal myself, I had to change my environment and reorganize my mind.

I fumbled through anything that might offer relief and wisdom. That led me to Zen practice. I now practice Zen Buddhism in my daily life, work as a meditation instructor at a Zen center, and I share stories.

Talking about Zen is challenging. There are many misconceptions, primarily that Zen practitioners are “always calm.” Zen brings you face-to-face with what is and who you are, but it makes no promise of enlightenment or accomplishment: the capitalist, magazine-cover concept of “perfection” fits on zen as well as shoes on our ears. Zen practice is straightforward: you sit and pay attention. If you’re anxious, you pay attention to your anxiety. You do the same if you’re elated or aroused.

On power of mediation

Gint Aras: When you meditate, you learn to notice the difference between the feeling you’re having…say, sadness…and the consciousness that allows you to observe yourself feeling sad. That consciousness is where you sit. It’s the one that helps you see “sadness” is just part of you, not all of you. Relative to your sadness, there’s a lot more to you, and sadness begins to look small, its power diffused.

Of course, the same is true for your elation. A lot of sadness is the result of our desire to be constantly elated. When you realize you’re sad because you want your life to be a magazine cover, you should roll over laughing. Our desire to be perfect is hysterical. To quote a Zen master a friend of mine drove to the train station: “What do you do when the Zen master farts in your car? You open the window.”

As far as writing goes…meditation and writing are similar states of mind. Writing is a kind of thinking whose focus is a single word: the one in front of you. That word is fleeting; it ends almost as soon as it has begun, and what follows is another word. The words just are: they’re neither being created nor destroyed.

Meditation is the observation of something similar, either the breath or some anchor that lets us perceive the flow of time. What’s different is that the process is not an effort, and it has no outcome that anyone besides the meditator can consider. If you’re considering an outcome, you’ll have a good laugh.

Your writing has a natural fierceness. Has that always been a part of you, or has that evolved?

Gint Aras: I’m not sure. Writing anything of consequence—a love letter or a job application—is an act of courage and vulnerability. I’m not consciously sitting to write and thinking, “Ok, be fierce.” That said, I understand the nature of the question, and I know what people find fierce in my writing.

I realized in childhood that the most radical thing one could do was to ask obvious questions. I mean things like this: Were the Lithuanian-Americans who protested the Soviet Union between 1989-1991—I was among them, mind you—fighting totalitarianism, or were they just fighting enemies? Is autocratic rule ok if it works to your benefit?

If you’re Lithuanian-American, will any of the immigrants in your family (or will you yourself) consider a move toward dictatorship if it entertains the fantasy of an America without people of color? When you ask how immigrants and their children can support tangents to the very political philosophies that led to the razing of their village, the deportation of their own relatives to Siberia, the torture of dissidents and the displacement of an entire generation, you’re labeled fierce. The alternative—timidity or politeness—is to sit quietly and observe without daring to offend someone’s support for the abhorrent.

The interesting thing about your question, at least from where I stand, is that I feel my energy pales in comparison to the ferocity of readers. Publishing is a game that goes something like this: Publishers and readers say, “Give us what we want!” Writers ask, “What do you want?” and the world stands in unison to scream, “We don’t know!”

What we really really want?

Gint Aras: Of course, all of us know exactly what we want. We are at best unable to admit it, at worst blatantly lying. Contemporary readers want two things. First, they want narratives that associate them with sociopolitical factions they consider righteous and correct.

Second, they want narratives and authority figures to validate their political points of view and aesthetic tastes. In short, they want to be right while feeling their political and cultural enemies are wrong. They hope writers will make this clear.

There has always been a bigger market for correct answers than for difficult questions. But today’s stakes are different because we’re living in times of cultural degradation, at the threshold of an extinction event hardly anyone wants to face.

Contemporary society is in dangerous denial: we displace responsibility and scapegoat even when we’re jaded, deluded, depressed and anxious, concerned that everyone is looking at us when we’re paying little attention to anything else. Our need for dopamine and our obsession with brevity and immediacy have broken our ability to perceive reality.

The two family members at your next dinner party who argue over the Mueller report—with one claiming it exonerates a demigod while the other says it damns a demon—both share one important thing in common: neither has read the report.

They understand it from snippets of bad summaries, communicated by media interested in giving people what they want. Those “information sources” stoke the very fear and fury they poach. It has become a cycle of frenzied, impassioned mass ignorance.

A lot of novels and memoirs operate under this desire to get people what they want instead of asking the obvious questions. I’ve never had much use for them. I don’t think a novel or memoir should be a “desirable product.”

You don’t resolve the issues they bring up by taking them to the customer service desk. Really…I started reading novels when I was in 2nd grade, and I’ve always preferred the ones that brandished blades instead of credit cards. I’d rather a writer bleed me than offer me coupons.

You’ve incorporated your childhood, raised by Lithuanian immigrant parents, and the first generation American experience into your work. In your upcoming memoir, it is shared in a way not taught in Lithuanian-American textbooks, but from the way you honestly, and actually experienced it. Gint Aras, how did it feel to share those brutally honest expressions of thought?

Gint Aras: Without giving away spoilers, my forthcoming book recalls my 2017 visit to Mauthausen, the infamous concentration camp in Upper Austria, alongside my upbringing in Cicero, where I grew up among Lithuanian displaced.

It details the formation of an identity that was based on an abridged, highly edited—I can say censored or cleaned—version of Lithuanian history, something that became apparent to me in young adulthood, when I got confronted by people who had much more information that I did. These confrontations forced me to change how I understood my ethnic identity. Ultimately, I started questioning the very nature of ethnicity, and of identity itself.

To me, both The Fugue and Finding the Moon in Sugar, if you read those novels carefully, handle similar questions, primarily of collapsing identity, and how the constructs of nation and religion, crossed with trauma, affect the composition of a self.

The big difference between the process of writing those books and the current one has to do with the presentation. Relief by Execution is non-fiction, so the veneer of artifice is much thinner. I have plenty of experience with non-fiction: I maintain a blog, and I’ve written dozens of essays, often about intimate themes.

That said, there’s something safe and fortifying about the disguise of fiction, and by comparison to books, essays of a few thousand words feel ephemeral. The process of composing and publishing a memoir feels like complete nudity, all my scars and broken skin on display.

Ultimately, I think the book is about the relationship between failure and agency, ego and insight. It’s liberating to write about failure because writing is an obvious act of agency. Writing helps catalyze failure into something else: if not a success, then at least a conversation. It’s hard to live with errors by yourself, and I suffered from horrible errors of perception for much of my life.

Can you share your own personal opinion of the Lithuanian damaged hero narrative, shared to first generation Lithuanian-Americans as they grew up? The honors still remain in our shared ancestral homeland. Gint Aras, several “heroes” still have streets and monuments named after them, even though mounting evidence indicates that they actually did a lot of harm to part of Lithuania’s citizenry.

Gint Aras: It’s curious synchronicity that these questions of Noreika and his status as a national hero came up while I was composing Relief by Execution. I’m ashamed to admit, but I’m sadly misinformed, particularly about the details of Noreika’s life and work. However, when I come across the rhetoric of his defenders and accusers, I sense energies that are not all that different from the ones fueling so much of our pan-Western struggle over convalescence and owning up.

There are two common foundations behind someone’s decision to erect a political monument. The first is a desire to commemorate episodes of either power or suffering. The second is to control a narrative.

Rarer is the monument that admits error and works to process shame. I don’t know how others feel, but this rare monument is often far more powerful, allows a narrative where greater numbers of voices participate, and it creates a space that provokes respect.

There are certainly Germans who go to the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin to feel an affront to themselves or their culture, but such a German is exceptionally rare. All parties involved in the Holocaust—the victims, witnesses, perpetrators, and students—can come to the monument to feel sorrow, acknowledgment, forgiveness, unity, and remorse. The monument legitimizes all of us as human.

On the Holocaust

Lithuania suffered enormously over its history. However, the narrative I got when I was growing up was that Lithuania was harmed while harming no one, something that’s just blatantly false.

It would be easier to settle these questions if greater numbers of individual Lithuanians did not manage their shame over the Holocaust by either denying it, minimizing its importance, shifting blame or changing the subject. People say, “Again this topic? Let’s move on. It’s over.” It’s not over if people feel they have something to express, or if they feel a story has not been told to its completion.

The desire to control narratives and defend pride is what’s at stake here, I think. The legitimate possibility to deny or minimize the Holocaust in Lithuania has essentially collapsed for all but the most extreme nationalists. In the wake of such collapse, the next step is to begin a battle over who had it worse, or who are trying to minimize whose suffering.

People don’t want to let go of memorials that represent power or resistance in the face of aggression, which is what I intuit Noreika’s defenders are claiming. When someone comes around to say, “Your man made my people suffer,” a common retort is to say “We also suffered.” Then it becomes a contest of who had it worse, with the assumption that the worse off party has authority over the question, so people clamor to put their victimization on display.

Of course, there’s a deeper psycho-social issue here. It transcends any discussion of any single monument, any single perpetrator of a crime, or whether we can be allowed to memorialize those who fought our enemies on one side of a conflict, even as they slaughtered innocents on the other.

I spend at least a month out of every year in Lithuania, and I’ve been taking my children there for over a half-decade. While attending the Summer Literary Seminars in Vilnius in 2014, I met a translator, a Lithuanian Jew, whose daughter became friends with my children. Because of these relationships, my kids have no problem with the idea that Jews can be Lithuanian. It’s hardly a topic.

My kids and Lithuania

The kids speak Lithuanian together. They have all picked wild strawberries in fields, stringing them onto shafts of grass. They’ve eaten šaltibarščiai (cold beet soup) in a village. They’ve run around the Vilnius Old Town for hours with other neighborhood kids and their dogs, all while their parents sat drinking tea on a balcony overlooking Literatų Gatvė. None of the people I’m describing, from the youngest to the oldest, have any problem with the (innocuous, obvious, simple) idea that a Lithuanian can be Jewish.

Let’s set aside a discussion about the Holocaust for second and limit it to ethnic or cultural identity. One privilege that Lithuanian Americans of my generation shared was the capacity to travel, often as early as our teen years, to all sorts of Lithuanian diaspora activities.

I’m talking about camps in Big Bear, California; festivals in Hamilton, Ontario; athletic tournaments in Chicago, Illinois; and an AABS conference in Stanford University, the latter drawing people from as far away as South Africa, Brazil, and Australia.

I’ve met South Side bar-room drunks who could not find Nemunas on a map, yet they identified as Lithuanian. I knew a homosexual Jesuit who could not pronounce Šventoji Marija, yet he identified as Lithuanian. A college basketball player who lived his whole life in the suburbs of Detroit, knows less than 100 Lithuanian words? Ditto.

The kids of WWII refugees who ended up in Buenos Aires? Quite. Girls born in Dublin to migrant workers who never saw reason to return to Utena? Social media pictures posted on February 16th show them with Lithuanian colors in their braids.

On ethnic and national identity

Gint Aras: Despite the complexity of ethnic and national identity that all these people share, to this day so many of them believe Jews cannot be Lithuanian. This should stun us. They’ve gathered a narrative that says Lithuanian Jews are—and I’m using the present tense with conscious ferocity—interlopers, nomads, migrants or enemies. The narrative deletes the possibility of seeing Jews as run-of-the-mill neighbors with tomato plants on their balconies.

That assumption, of Jews as other, often forms the subconscious foundation to any discussion of the Holocaust, and people don’t even realize they’re talking in different terms. Compare these statements: “Look what these people did to their fellow countrymen” versus “Look what these people did to their enemies.” Look what they did to these nomads, migrants or interlopers. Compare that to this: “Look what these people did to their neighbors.” Then there’s this one: “Look at what these people did to their fellow human beings.”

At the heart of any provocation to discuss atrocity lies a simple goal. Can we learn to see each other as entirely and truly human? Can we set aside our filters and fear to see that this discussion is not an attempt to grab or acquiesce authority?

If I acknowledge the Holocaust took place, and it occurred because of widespread anti-semitism, I’ve not diluted my blood. The only way I can betray my tribe is if the tribe expects me to maintain a narrative that’s based on a dehumanizing point of view. If that’s what I’m doing, I have no problem betraying the tribe. It’s not any tribe I want to be part of.

Point blank. I know Lithuanian-Americans—some of in my family—who think Jews cannot be Lithuanian. If you accuse them of anti-semitism, they become furious. It’s exactly the kind of fury that erupts from certain people who don’t want to hear women complain about sexual harassment, or minorities complain of police brutality.

It’s no different from the accusations people levy at rape victims: she wore the wrong tank top, or her skirt was too short. It’s the same fury certain fans of Penn State pointed at the press for reporting and documenting that a cultural hero was helping cover up a pattern of heinous crimes. There’s a subset of our society that automatically identifies with perpetrators of crimes, and they perceive outspoken victims or thinkers as threats. Of course, threats to what? There’s a ferocious question.

Gint Aras, What is next for you?

Gint Aras: I’m hoping to do some collaboration with some international artists. I also have a long term plan to write a comedy about American education.

Could you share a bit about the comedy? It would be very interesting to see this side of your writing. Gint Aras, have you started on it yet?

Gint Aras: I’ve not started it. I have to publish some short pieces first to gauge just how badly my college will want to fire me for pointing out the obvious.

In short, American Education is a comedy. The sausage is made with Monty Python meat.

Here’s an example:

Virtually every college president in America has a secret fantasy to eliminate human teachers altogether. Human teachers either interfere with the maintenance of a kleptocracy, or they steal things like printer paper, laboratory acid, and instant coffee. Community colleges have been handling this by eliminating full-time instructors and replacing them with part-time adjuncts who have fewer sets of keys. They are paid a bonus of popcorn on top of peanuts, worked so hard that they don’t have time to scheme a heist of printer paper. Ph.D. programs know this—part-time teachers in Ph.D. programs know this—yet they continue offering Ph.D’s.

In the meantime, colleges are experimenting with computer-based modules and online education that uses standardized answers and processes, which even crude robots can check for “correctness.” The trick now is to convince college students that education is just as valuable, perhaps even better, when taught over the very cell phones that make robots of them.

If colleges could do this, they could keep the peanuts and popcorn for themselves, distribute the snacks to their friends, and hire even more assistants to the assistance of the deans, all of whom are assistants to the provost, who is an assistant to the president, who sits eating sausages made of Monty Python meat.

Colleges will shift from fighting online sales of essays and dissertations to simply selling these dissertations to students themselves. Students won’t even need to see the dissertation (it probably won’t even exist). To pass any class, you’ll just show a bar-coded receipt. Even doctoral students will be able to do it. They’ll be allowed to use their cell phones.

The college will still require all the assistants to sit in contractually mandated meetings. No subject will be presented, no comments will be made, no discussions will take place. The kleptocrats’ need of keeping people silent, dehydrated and sober in a poorly ventilated room for three hours and against their desires will remain sacrosanctly.

This vision for the college is genius, really. Hallways full of young people staring at cell phones, heaps of money dumped into a Chinese doll of assistants, a president constipated on Monty Python meat, no human teachers to be found anywhere, but the weekly meetings full of people contemplating suicide will still take place. It’ll be more lucrative than a private prison. And you can bring your cell phone.

It’s a dark comedy. But it’s still funny.

I sincerely and respectfully thank you for your time in sharing your thoughts and your perspective. Looking forward to the release of Relief by Execution: A Visit to Mauthausen.

Be the first to comment