The structure of the economy and the education of Lithuania’s current society is failing to ensure adequate returns on investments by the state into facilities, laboratories and equipment in the high-tech field, according to economist Stasys Jakeliūnas. He and fellow economist Romas Lazutka agree that, while investing funds and effort into high-tech development and expanding its share of the nation’s economic structure, Lithuania should not forget its traditional industries.

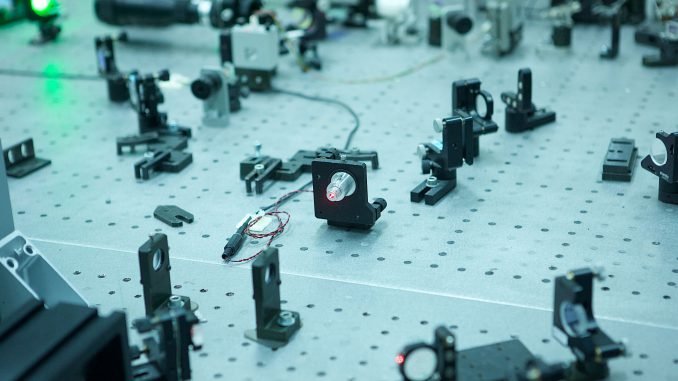

“Today, Lithuania does not have the [skilled] people and is not in a position to take advantage of [large state] investments into high tech. They will simply be wasted. We already have such examples – some of our ‘technology valleys’ have been heavily invested in but much equipment was purchased is rarely used by scientists or businesses.

“Of course, it is hoped that the facilities will be used more, but we have operated and continue to operate under the idea that ‘there’s money, so we have to use it’ – I’m referring to projects supported by EU funds or other subsidies,” said Jakeliūnas.

Relying on illusions

When the Lithuanian government sees that its innovative product development and export performance is two to three times lower than those of our Baltic neighbours, like Estonia, Jakeliūnas said it believes that it can improve those metrics and become competitive simply by investing large sums of money.

“This is mostly an illusion, though I’m not saying that shouldn’t be done. The investment needs to be done, but carefully, with rigorous evaluations, and by starting with ideas, people, projects that then get funded, and not the other way around, as they do now. The returns on these ‘technology valleys’ need to be calculated before investing money into them,” Jakeliūnas said.

The fundamental foundation of a country’s economic structure is people and their education, according to Jakeliūnas, along with the country’s ability to attract people from abroad, and its ability to attract educated Lithuanians working abroad.

Don’t expect a revolution, but encourage one

Economist Romas Lazutka emphasised that the transition to a high-tech-oriented economy should happen step by step. Today, Lithuania lacks the right skilled IT professionals and potential jobs to make it happen.

“Currently, there are complaints that few young people are choosing to study engineering specialties. Why should they choose engineering when they will have only three companies in Lithuania to choose from when they finish their studies? What should they do when they don’t get a job? Works as managers at shopping centres and manage five salespeople?” asked Lazutka.

“On the other hand, if those people don’t learn those subjects, then those companies won’t be able to form. Therefore, there can’t be any sort of revolutionary leap, but the state’s policies can encourage these things,” said Lazutka.

While there is a bit of a chicken and egg situation, he emphasized that it would be wrong to discourage people from entering engineering or high tech training as there is a need for a suitably trained pool people for high tech companies to be attracted in and be established but it had to be a transition process.

Don’t forget traditional industries

According to the two economists, the state should not forget traditional industries in its push to support high-tech industry but remaining a “factory-state” was no solution either, as this would mean that wages would remain low.

“Our industries currently consist of medium and low tech. It’s understandable that it’s hard to expect large wages when orienting the country’s economy towards industry. China is an example of one such ‘factory-state.’ Its economic growth is impressive, but people there live poorly, there is extensive inequality, and its average wage does not reach Lithuania’s.

“We need to move in both directions – high-tech and development of traditional industries,” said Lazutka.

Jakeliūnas emphasised that the vast majority of people have always been those that can memorise and carry out instructions, rather than those who can create new global technologies and other products, so investments shouldn’t just focus on the high-tech sector.

“We need to look ahead and think about technologies, but we shouldn’t run ahead, especially with our [limited] finances. By failing to use our money effectively, we can discredit an idea and demoralise businesses and the economy,” he said.

“The goal of higher education should be people who can create, not those who can learn and carry out instructions, though the majority of them will be the latter. A creative person should be the goal from kindergarten. And then, if we have people who can create products and offer them to the world, the investments will come on their own, we won’t even need European money,” said Jakeliūnas.

Be the first to comment