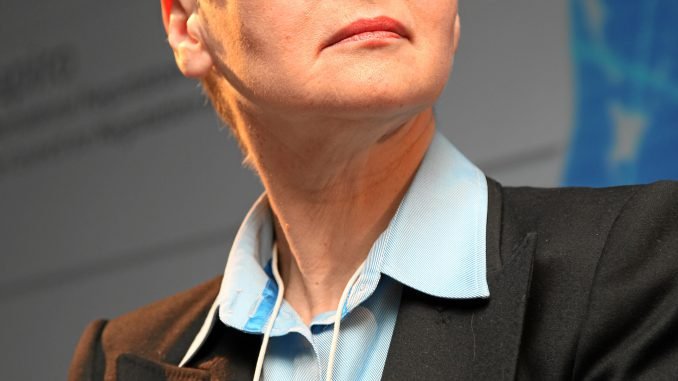

“Right now, Putin reminds of a reflection of powerless omnipotence,” Shevtsova says in an interview to DELFI.

She adds, however, that there might be a silver lining to the Kremlin’s recent aggression. According to the senior fellow of the Brookings Institution, an influential US think tank, if it were not for the shock therapy provided by Russia’s recent actions, the West would still be in deep slumber.

“The post-Cold-War period with its ideological uncertainty, striving for the status quo and stability, conviction that the West do not have genuine opponents and adversaries, is over. Putin has kicked the entire chessboard. I’d even venture to say that Putin did a good job, because otherwise the West would have stagnated even longer,” Shevtsova said.

This week, Lilia Shevtsova is taking part in the forum discussion “Russia and the West: Reality and Perspectives” in Vilnius organized by the Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Eastern Europe Studies Centre.

When it comes to explaining the inner workings of the Russian regime, a popular metaphor to use has been the mafia structure. According to this concept, Putin is a capo dei capi of sorts, someone mediating between various clans and arbitrating in their conflicts. Would you subscribe to such a view? If so, how stable do you think this regime is, can there be clans that pose threat to Putin?

True, mafia-type psychology, behaviour and mechanics can be characteristic of any one-man regime. The samoderzhaviye – personalized power – that is characteristic of the Kremlin has a long and blood-stained history, it is based on a tradition of subjecting everyone and drowning everything in mist. It does remind of what is described in Mario Puzo’s novel “The Godfather”, but it also gives a simplistic view.

First, there is no need to depict Putin as an efficient and shrewd dictator. He is a shallow mediocrity who ended up in the Kremlin by accident. Granted, he has learned to find his way around its corridors, but he failed to come up with a way to run a state in the 21st century.

Second, we can see today that the Russian capo dei capi feels lost, disoriented and unaware (without a clue!) of what to do with Russia that is on track to an abyss. Right now, Putin reminds of a reflection of powerless omnipotence. The 80-percent support for him from the population does not mean anything – all authoritarian leaders enjoyed massive “support” before downfall.

True, before losing ground, such a regime and its leader can become even more dangerous to its own people and the external world. Especially when he is trying to survive by pushing the country into the war paradigm. In any case, we are witnessing the beginning of the agony of this regime that will be painful for Russia. This agony can bring changes in the regime that will perhaps help the system of personalized power to reproduce itself.

When it comes to Kremlin clans, I only see one that obeys Putin. True, there are divergent interests among the Kremlin’s inner players, animosity and competition exist. One can say that interests of various Kremlin elite groups do clash. But it is hardly likely right now that any one of the Kremlin groups is ready to reject the personalized power system and liberalize Russia. Therefore when Putin loses control, we are likely to see a continuation of this same one-man power. Unless the anti-system powers in the Russian opposition manage to consolidate and rally to form a powerful force.

Russia is moving towards a crisis and this crisis will create new reality. However, Russia will probably have to go through hell before we see a real, not illusory way out of this. The positive thing is that over 60 percent of Russians, whose situation is deteriorating, are not ready to pay for Russia’s “greatness” and Putin’s war. Therefore the militaristic drug is wearing off.

There are voices saying that Putin is the best choice for the West, because his successor might be even more aggressive and make confrontation inevitable. What do you think? Would the West indeed fare better by sticking with Putin than the unfamiliar leader who might come after him? Do Western leaders have a strategy for a post-Putin Russia at all?

The West must be concerned and fearful about the future of Russia and the current regime. This is understandable. The fall and degradation of the nuclear state of Peter the Great, a torpid empire, might become a real challenge for the twenty-first century. Neither the Russian society, not liberal democracies know how to react to that. My guess is that the West are now facing a dilemma. On the one hand, Putin presents a threat to the West, but not because of his arrogance. More importantly, he is unable to control Russia’s decline and has found himself (to his own surprise, probably!) on a bob-sleigh track – he cannot change the course. He already resembles a leader who plays a suicidal role in state governance by harming his own country.

On the other hand, no one can say who will rise in Russia after Putin’s fall. He has opened a Pandora’s box and showed the Hobbesian world of war of all against all. He has destroyed the rules of the game – in Russia and beyond. Now he is legitimizing his power by breaking rules!

I think that the West is trying to find a balance between Russia’s containment and dialogue with the Kremlin in an attempt to avoid aggression. This, of course, is a reactionary policy. Truth be told, I do not believe that the Western powers are in possession of any tools to predict what will happen next (nor are the Russians) or lead proactive action vis-a-vis Russia: we are in the middle of uncontrollable and unpredictable history. At least the West could try to maintain unity in their reactions – it would already be a big achievement.

War in Ukraine started for more or less clear reasons – Moscow resisting the expansion of Western – the EU’s and NATO’s – influence. Do we know what Russia is after right now?

You know, I doubt that the central element in this war was the European Union and NATO expanding their influence. Believing that would mean accepting the Kremlin’s version of events. This explanation raises several questions. Why hadn’t Putin expressed concerns about the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement even once back when it was still in the works (and it was for years). EU leaders, including José Manuel Barroso, said that Putin had never raised the issue! Why was the Kremlin so irritated by the treaty with Ukraine and not at all worried about the EU’s agreement with Baku?

Another question: Why did Moscow suddenly become so unhappy about NATO at the point when the alliance was losing its central mission and turning into a thing of the past – it had even stopped expanding!

I think that the main reason behind the war was the Kremlin’s new survival doctrine based on containment of the West, but this turned Russia into a besieged fortress. This happened in 2012-2013, before the Maidan in Ukraine. The Ukraine crisis and Viktor Yanukovych‘s fall became testing grounds for Putin’s doctrine whose origins are purely domestic.

Economic sanctions usually work as a threat or long after they are applied. I cannot recall, however, a case of sanctions helping achieve political goals. What is your take on this?

The West or the United Nations have instituted sanctions against about 28 countries. Sanctioning is a tactical instrument, therefore it is true that there is not a single case in history of sanctions helping bring about a regime change. Apartheid in South Africa could be the only example of sanctions really doing the job they were intended for. I think, however, that sanctions can be used to change a regime’s policies – like it happened in Russia. Sanctions were among the reasons why the Kremlin gave up the “second Crimea” scenatro in south-east Ukraine.

Some experts claim that sanctions help Putin consolidate the society, but I think that their effects can be two-sided: at first, they might have helped the Kremlin, but sooner or later they will bring an increasingly severe crisis that will destabilize the regime. Either way, if we hadn’t introduced the sanctions, how else could we have stopped the war that the Kremlin started?

EU external affairs representative Federica Mogherini recently said she saw “positive signs” in the Ukraine conflict. Lithuanian Foreign Minister Linas Linkevičius responded that he did not see any such signs. What do you think?

This probably depends on the criteria you use to define “positive signs”. If the main criterion is Russia having stopped open military invasion in Ukraine, like when its regular forces were openly violating the border in August 2014, then we can indeed see positive signs.

The fact is that the Kremlin has altered its course in Ukraine. Putin now wants to have the insurgent east regions incorporated into Ukraine as a partly independent unit. It would serve as a dagger in Ukraine’s body or as an unhealed wound able to destabilize the Ukrainian state. Moreover, the Kremlin will (and already does) experiment, employing other types of military measures – information, trade or customs war. It will co-opt the corrupt echelons of Ukraine’s elite and try to deepen the crisis in this country.

Therefore, when it comes to Russia’s pressure on Ukraine, I see no progress. I think that Mogherini and the European Union should use broader criteria for Russia’s aggression against its neighbours. The Kremlin’s ingenuity and machismo trumps the European Union’s expertise.

You wrote last August that Putin ended the interregnum period and ushered his country into a new era. What era is that?

The post-Cold-War period with its ideological uncertainty, striving for the status quo and stability, conviction that the West do not have genuine opponents and adversaries, is over. Putin has kicked the entire chessboard. I’d even venture to say that Putin did a good job, because otherwise the West would have stagnated even longer.

The new age requires Big Thinking – we need to return to normativity, to reform the liberal system, to revive the trans-Atlantic partnership, get the new leadership back on stage – to have leaders of change. Putin has woken the West up, but the West must reinvent itself anew as an alternative to the non-liberal world. Otherwise we will slide back to slumber.

Could you compare Russian policies of Barack Obama and Angela Merkel? Merkel comes across as a comprehensive leader, but for how long, do you think? The German business establishment does not have limitless patience.

By turning away from the outside world and declaring a reset, Obama did not win anything, Russia’s turn to Western containment must have come as a shock to him. He obviously chose to ignore Russia with Putin. We could simply observe Obama’s reluctance to take any action or make decision in the beginning of 2014. Only Congress made him act, realizing that America’s non-reaction will cost Washington much more in the future.

I guess that Obama was a big factor that pushed Berlin and the European Union into adopting sector-specific sanctions, even though Chancellor Merkel tried to avoid cornering Putin. When he signed the Ukraine Freedom Support Act, Obama showed his readiness to consider a new round of sanctions.

We are witnessing today an unbelievable transformation of the German chancellor, she deserves to be Person of the Year. She went from policy of patience and appeasement to one of Kremlin containment. She is now the one who makes real decisions in Europe, a force that ensures Europe’s unity behind the sanctions.

At the same time she tries to balance Russian containment and dialogue with the Kremlin, which is a hard task. The fact that the Kremlin lost German support in the West was a big hit to Putin. He could have hardly expected that the Germans would change their view on the Ostpolitik. Indeed, we can just imagine the sheer pressure that Merkel is experiencing from various groups of Russian advocates, but she cannot revert back to “Shroederization”.

What do you think of the challenges for NATO’s eastern members? In Lithuania, we think of ourselves as a geopolitical miracle. Could Lithuania even think of being admitted to NATO under today’s conditions?

Recent events have confirmed that the decision of the Baltic states to become NATO members was the right one. Just imagine, had they not joined NATO when they did, today they would be in a situation similar to Ukraine’s. As we can see, the collapse of the old empire is far from over.

I seriously doubt that under current circumstances the Baltic states could become members – why should the West put itself in danger of confrontation with Russia?

The Baltic states are also situated on a civilizational (not geopolitical) fault line, which accords them a very important role.

First, they must explain to the West what is actually happening in the post-Soviet space. They feel it with their fingertips.

Second, they must lobby to implement reforms in Ukraine. Third, they should think of how to create favourable external environment for transformations in Russia. Fourth, they are the West’s experiment ground and the significance and essence of their security have changed substantially. Quite a challenge!

Be the first to comment